The golf industry has changed significantly over the past couple of years. While the commercial real estate market is trying to figure out how to restructure more than $400 billion in loans that are coming due in 2009 nationwide, golf was hit hard by the announcement that Textron Financial was pulling out of golf course lending. Also sidelined is Capmark Financial, the other major player in national golf lending. This coupled with the loss of other major golf lenders, like Pacific Mutual and GE Capital, leaves this product type without a national lender. This is critical because multi-course owners with assets in several states will struggle to find a source of capital to accommodate future acquisitions and refinances. Local lenders are stepping up but not on a nationwide platform. The loans that have been made have been relatively small in size ($), local in nature, with traditional loan to value ratios and with guarantees by the borrower. This is in stark contrast to the way in which the nationals had lent. With years of over building and now lower golf participation and difficulty in finding capital, golf is faced with the perfect storm.

According to estimates compiled by the National Golf Foundation (NGF), total rounds played in the U.S. have dropped off significantly from 518.4 million in 2000 to 489.1 million in 2008. The most dramatic decrease occurred in 2002, followed by a generally flat trend up through 2007, followed by another large decline in 2008. This has occurred as population numbers have steadily increased during this same time period, by approximately 1% per year. NGF has identified 72 golf courses, in 18-hole equivalents, that opened for business in the U.S. in 2008. During the same period, there were 106 golf course closures, resulting in a net negative of 34 courses. This represents three straight years when the number of closures outnumbered openings.

Nationwide, same course rounds were up 1.5% in 2007 yet down by 1.8% in 2008, while in New England there was no change in play from 2007 to 2008. For the most part, rounds have been generally flat, while at the same time revenue has declined slightly in many cases, suggesting that more discounting is required. Thus, the average price per round is down.

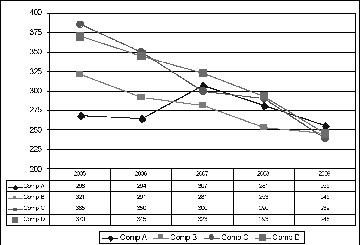

While for the most part, activity at public courses has held steady, private clubs have seen a continual slide in membership counts. With rising unemployment, concerns over job security, lower business profits and declining corporate sales, private club memberships have been shed. In Connecticut, for example, unemployment went from 4.8% unadjusted in April 2005 to 7.8% in April 2009. As the state saw about 60,000 people lose their jobs, private country clubs lost many of their members. The graph below shows the decline at several central CT private cubs. Most lost more than 30 golf members since the fall of 2008 alone.

Jobs and consumer confidence are critical to membership demand. Only when the economy improves and jobs are created can we expect to see growth again at private clubs. In the meantime, clubs continue to offer incentives, by reducing costs of admission. Golf Magazine last month (April 2009) included a lengthy article about high end clubs cutting initiation fee deposits, spotlighting Oak Hills Country Club, site of the 2008 PGA Championship and eight other majors, as it reduced its fee from $110,000 to $60,000. Locally, the Golf Club of Cape Cod began waiving its $85,000 initiation fee for new members in hopes of increasing revenue. During these tough times, private clubs are also finding ways to trim overhead. It is imperative that clubs cut fat from their budgets. Fortunately for most there are things that can be done. The maintenance budget is one of the largest and most labor laden departments, and food & beverage is often another loser.

Jeffrey Dugas, MAI, SGA is a principal at Wellspeak Dugas & Kane, Cheshire, Conn.

Tags:

Growth at private golf clubs will occur when the economy improves and new jobs are created

May 28, 2009 - Spotlights